- a reformation harder … less likely … but, in the end: DEEPER

This talk was delivered by John P Wilson, Clerk of Assembly, at the Bundoora Presbyterian Church on 5th July 2017.

1. Pre-reformation Scotland – why reform was harder … and less likely

3 factors: geographical, political, ecclesiastical.

a) Geographic isolation

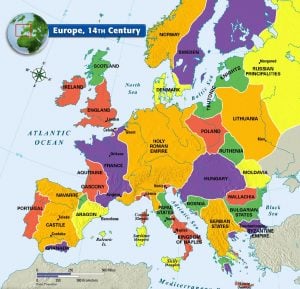

Both Renaissance and Reformation made spectacular advances on the Continent, and much earlier than in Scotland. One of the reasons for this was the geographic isolation of Scotland as compared with the European countries.

While there was regular contact by sea, especially to the Scottish merchant ports from the Low Countries (present day Netherlands and Belgium), yet there could not be the constant movement of people and ideas in the same way as on the Continent. Further, and in general, education was not as advanced as in Europe.

Nevertheless, during the period from 1517 to 1560 Reformation literature and ideas abounded, especially in the ports of the east coast, as sailors and merchants returning from Europe brought books and pamphlets with them. So, despite the geographic isolation, literature did find its way inland in the hands of merchants and travelers and a number of lairds and nobles* were won over to the Reformation cause during this period of time.

- lairds were Scottish land holders, owners of large estates

- nobles were leaders of Scottish clans (kinship groups)

b) Political alliances

Politics of the period also had a bearing on the matter, especially the long-standing connection with France. The relationship between Scotland and France is often referred to as ‘the auld alliance’ (the old alliance).

Scotland in the 16th century was a land in turmoil. It was by no means a peaceful or prosperous country. Not only was she affected by the constant conflicts in Europe which damaged her trade, but she suffered from the internal anarchy brought on by an unruly and self-centred aristocracy.

Squeezed between two great powers, England and France, Scotland in mid-century favoured France politically, therefore the Roman Catholic influence was strong. As strong as this old alliance was, nevertheless what was happening on the Continent was known in Scotland, and ideas started to penetrate there as well. These served to point to the need of reform within the church, and to open people to the new teaching of Luther in particular in regard to biblical teaching of the way of salvation.

There were early signs of reformation – and even a false dawn. Luther’s writings began to circulate in Scotland in the 1520s, and widespread stirrings began. Smuggled copies of Tyndale’s New Testament surfaced also.

In 1525, an act was passed prohibiting possession of such material. By 1540, sizeable numbers of Lutheran preachers and intellectuals had already left Scotland for England or the continent and most never returned. This early ‘reform’ movement reached its height in 1543 when Parliament, under the influence of the Earl of Arran* passed an act allowing all subjects access to the Scriptures in the vernacular. The Tyndale Bible, it was reported, was to be seen ‘lying almost upon every gentleman’s table’. A wave of popular iconoclasm directed against the religious houses swept through a number of the larger towns.

Yet this false-dawn reformation of 1543 was short-lived and premature. Its excesses provoked a backlash, especially amongst townspeople. Its political backing evaporated when Arran’s ‘godly fit’ came to an abrupt halt at the end of 1543 in a complicated palace coup.

* a high rank in Scottish peerage, from the island of Arran

c) The state of the church

The state of the church in Scotland was no better than on the Continent. If anything, it was worse. The ignorance of the clergy was significantly bad, and the leaders of the church were more concerned with financial gain and political power than in spiritual matters.

The historical record tells us that within the Scottish church preaching was virtually unknown prior to the Reformation. There are many witnesses to this fact, and in the poems of Sir David Lindsay (much-loved Scottish poet of the day) the clergy are frequently reproached for their inability to preach:

Great pleasure were to hear one bishop preech,

one dean, or doctor of divinity;

one abbot who could well his convent teach,

one person flowing in philosophy;

I tyne my time to wish what will not be,

were not the preaching of the begging friars

tynt were the faith among the seculars. (Tyne, Old English for ‘to perish’, or ‘to lose’)

Examples of clergy who could not preach:

Bishop Dunbar of Glasgow went to Ayr to counter the preaching of evangelist George Wishart. Knox says: ‘The sum of all his sermon was: ‘They say that we should preach: why not? Better late thrive than never thrive: have us still for your Bishop, and we shall provide better the next time.’ ‘ Knox adds: ‘This was the beginning and the end of the Bishop’s sermon, who with haste departed the town, and returned not again to fulfill his promise’.

Archbishop Hamilton of St Andrews was to preach in St Giles, Edinburgh, in 1559 at the time when the Queen Regent was trying to coerce the people of Edinburgh into restoring the old religion. After speaking for a little, he declared that he had not been well exercised in the profession [of preaching]: therefore he desired the auditors to hold him excused.

The immorality of the clergy was notorious, and two Scottish surnames still testify to this fact (MacNab, son of the abbot; MacTaggart, son of the priest, in Scottish Gaelic. Marriage by members of the clergy was prohibited after the 12th century and they took a vow of celibacy, but such vows were frequently broken).

The priests were poorly trained, and in general they did not have the scholarly attainments of many of the European clergy. While some attempts were made at reform, what was needed was a combination of political will and a ground-swell of popular support for the new teaching already at work on the Continent. Leadership was also an important factor, and the natural gifts and training of Knox proved to be crucial to the success of the Scottish Reformation.

But, we run ahead. These are but three factors: geographical, political, ecclesiastical, explaining why reform was harder … and less likely in Scotland. And so it might have remained were it not for one famous man under God.

2. John Knox – God’s trumpeter of Scotland

Another 2nd generation reformer

John Knox was born in Haddington, a small town south of Edinburgh, in the year 1514. We know almost nothing of his parents and as much as nothing about his childhood. As a 15-year old youth he studied at St Andrews University and went on to study theology.

He was ordained in 1536 (the year Calvin was first publishing The Institutes). But he did not take up a parish appointment because there was an excess of priests in Scotland. So he tutored some young boys of Scottish nobles.

We do not have any account of his conversion but we know that John 17 was most likely used to speak to his heart. On his death-bed he described John 17 as the place ‘where I first cast my anchor’. That’s about all we know of his early days! We’re to look at the shaping of this man John Knox, using four powerful life-shaping influences: church, fire, rowing, exile.

a) The church shaped him … Roman Catholicism in Scotland

The state of the church in Scotland was deplorable. John Knox recalled that Edinburgh in 1542 was ‘for the most part … drowned in superstition’. Many were angry with the Roman Catholic Church, which owned more than HALF OF SCOTLAND, and then gathered in so much tax for use of that land that the church’s treasury outweighed, many times over, that of their own King!

Bishops and priests were appointed and invested by favour and bribe, not giftedness or training. A man didn’t have to train to become a priest, and all too often, he was appointed by political favour and for gain. Many, though swearing to celibacy in their ordination vows, were immoral and had fathered children. The top churchman David Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews and Cardinal for all Scotland*, had many mistresses and had fathered at least ten children. Many priests couldn’t read and most had never read the Bible. One bishop said proudly:

‘Well, I’m glad I’ve never read the Old or New Testaments, it’s much safer just to have the book of order and prayer book.’

- David Beaton was handed the St Andrew’s position on the death of his uncle James Beaton

Knox was a priest in this church. He was part of it. In his youth, there was a wave of reform sweeping into the country and spreading like wild-fire. Constant sea traffic between Scottish ports and Europe meant that Luther’s literature was smuggled into the country. The Scottish Parliament was determined to put an end to Luther’s influence and stamp out his teaching.

For example, the King’s* cousin, Patrick Hamilton, sponsored by Parliament, was sent to Wittenberg to investigate all this new teaching so that they might be better informed about it. The problem was (for the King), Hamilton was persuaded by Luther and fully embraced reformation doctrine. He said:

‘I have found the long-buried truth’

- King James 5th (son of James 4th & Margaret Tudor); James 5th married Mary of Guise and they had an infant Mary Stewart when he died in 1542.

On his return back home, the Roman Catholic leader in Scotland, Cardinal Beaton, had Patrick Hamilton arrested and then burned him at the stake outside the ancient college of St Andrews in 1528.

From 1528 – 1560, about 20 reformers were burned at the stake. Their deaths only increased the Protestant feelings in the country.

While not saying that Patrick Hamilton, the first public martyr of many, was on Knox’s radar at the time (he was only 14), but this is the Catholicism that Knox entered into … and loathed. But one of the martyrs WAS his best companion.

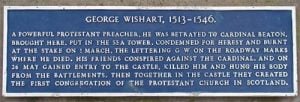

b) One of his best friends shaped Knox

One of the martyrs was the godly and much-admired George Wishart. As a teacher, Wishart taught his students to read from the Greek New Testament and was promptly charged with heresy. Wishart said: ‘Well, never mind that’ and gave lectures on how to preach from passages of the Bible. He preached, bravely, in the open air – anywhere he had a hearing. As a field preacher, Wishart had to keep moving to dodge Church officials. John Knox was friend and bodyguard for him and remembered him as:

‘a man of such graces as before him were never heard within this realm, yes, and are rare to be found yet in any man’

As bodyguard, Knox had to push the preacher here and there, in danger from assassins and informants. Knox carried a two-edged sword and was constantly by Wishart’s side. Here, he spent day and night with this man, guarding him from harm, listening to his every word, praying with him. Then in 1545, Knox’s conflict deepened when George Wishart was arrested by Cardinal Beaton and then tried.

Knox wanted to go with him. Wishart said:

‘No, return to your pupils, and God bless you. One is sufficient for sacrifice.’

Wishart did not go quietly. On route to public execution he said:

‘Although I will be briefly pained in my body, I shall shortly be kneeling at the feet of Jesus, safely in heaven with him for eternity.’

Cardinal Beaton had Wishart bound and burned, outside the castle of St Andrews. As the flames rose Wishart called out for the forgiveness of those who lit the fire.

This GW marker is on the road immediately outside St Andrews Castle

It is said that the martyrdom of Knox’s friend Wishart profoundly moved and turned a nation. The imprint on Knox never left him.

In retaliation, 2 months after the burning of Wishart (and no one condones what happened next) … Cardinal David Beaton was stabbed to death by a group of revolutionaries (John Knox was NOT one of them). But he was certainly ‘on the side of the revolutionaries’ and later, after the murder, joined the group who had stormed Beaton’s castle and taken it over. Somehow, Knox was smuggled into the castle, because by then it was under siege by the French army. And he was appointed their preacher. So begins a short ‘parish’ ministry of the Castle of St Andrews.

the ruins of St Andrews Castle

c) 18 months as a galley-slave rower helped shape Knox!

It was a short-lived rebellion because eventually the French Army stormed in and took all the Protestants captive. Knox was taken prisoner by the French. Yes, there is complicated political background to this …

The greatest rivalry of 16th century Europe was that of Spain and France – and the two kingdoms of the British Isles (England and Scotland) were peripheral players. But there were certain contexts in which they can harm or hinder the main contestants, And so if France thought that Scotland is in danger of being out of control with its Reformation radicals, then it was entitled to step in and deal with them.

And, of course, royal marriages with France and Spain were used by both countries to reinforce their potential alliances. England’s Henry 8th first married the Spanish Catherine of Aragon and yet, in 1514, he arranged a match for his youngest sister Mary with the French King, Louis 12th. Later we even note the farcical double proposal by each of Henry 8th and James 5th of Scotland for the ‘hand’ of the French princess Mary of Guise. (Clearly, James of Scotland won out*.)

* On the one hand: Scottish James 5th had been widowed and was seeking a second French wife. On the other hand: the English Henry 8th was also widowed as Jane Seymour died from complications from childbirth late in 1537 (her son, Edward). So Henry, in attempts to prevent the Scottish – French union, also asked for Mary’s hand. Given Henry’s marital history – banishing his first wife and beheading the second – Mary refused the offer. In December 1537, Henry told the French ambassador in London, that he was big in person and had need of a big wife. It is reported that said Mary replied, ‘I may be a big woman, but I have a very little neck.’ This was apparently a tribute to the famously macabre jest made by Henry’s French-educated second wife, Anne Boleyn, who had joked before her death that the executioner would find killing her easy because she had ‘just a little neck.’

These matrimonial negotiations are part of the wider diplomacy of England and Scotland in Europe, involving military alliances and sometimes war.

So, in this mish-mash of political intrigue, with the French wanting to keep Scotland Catholic, Knox and the other Protestants were carried off to serve as galley slaves in the French fleet. Knox survived nineteen months of this before he was released.

32 years of age, chained to a bench and forced to pull at a heavy oar under the lash. Through the bitter cold of two winters and the heat of the intervening summer. It was a death sentence: chained to hardened criminals in the most unhealthy of conditions, abused, mistreated … most rowers died. There’s some thinking time, to reflect on the cost of being Protestant. But his faith never wavered.

One day his master of the galley insisted that all galley slaves kiss a carved image of the Virgin Mary. To get the full picture of this incident: the ship was called the Notre Dame (‘our lady’, i.e. the Virgin Mary). Knox refused, but picked up the idol and threw it out to sea saying: ‘Let Our Lady now save herself. She’s light enough, let her learn to swim!’ It’s a wonder that Knox survived. After many months he found himself weak and emaciated.

After rescue from the French galley ships, Knox was like a man not knowing where to place his head at nights. He dared not return to Scotland where his reformed preaching had made many enemies. South of the border, Edward 6th of England had set about godly reform of his kingdom and he authorised Archbishop Cranmer to recruit the very best preachers from the Continent and send them out to villages far and wide to preach the gospel.

It was in this way that this emaciated, single 34 year-old man was sent to Berwick to preach and there met the love of his life. Soon afterwards, he married the 19 year-old Marjorie Bowes and they settled for a while in England where he resumed as an evangelical preacher. John and Marjorie Knox had two sons: Nathaniel and Eleazar.

d) His years in exile served him well – fearing for his life

Unable to return to Catholic Scotland, the preacher was welcomed in England. The kingdom was then experiencing its first real period of reform under Edward 6 (1547 – 53). Knox travelled around the country spreading the faith. Knox was one of Edward’s favourite chaplains. Edward offered Knox a position as Bishop.

His influence was such that historians believe that he inserted into the English Prayer Book (just before its printing) a footnote explaining that as the communicant kneels to receive the Lord’s Supper ‘no adoration is intended or ought to be done either unto the sacramental bread or wine.’

But the accession of the very Catholic Mary Tudor in 1553 forced him to flee for safety to the continent, 1553 – 58. He ministered to refugees in Dieppe and Frankfurt and settled eventually in Calvin’s Geneva.

John Calvin says of Knox: ‘our brother, labouring energetically for the faith’

Knox said of Calvin’s Geneva:

‘the most perfect school of Christ that ever was on earth since the days of the apostles’

Knox was safely in Geneva, but he was never quiet. Far from home, but never silenced. From Geneva he writes a notorious tract: ‘Against the monstrous regiment of women’ in which he particularly attacks the English Queen Mary who had been burning evangelical preachers on the fires of Oxford. He calls Mary Tudor:

‘most odious in the presence of God … a traitoress and rebel against God’

This was a short description of the emergence of Scotland’s greatest, John Knox, and how God used four powerful life-shaping influences: church, fire, rowing, exile.

3. Reformation in Scotland

a) The Scottish-French alliance

In Knox’s absence on the Continent, during the late 1550s, Mary Guise (who was in fact the Queen mother) was ruling Scotland with the assistance of the French.

We do need to pause here and recap our knowledge of the royal family. James 5th, the King of Scotland, had married a French princess, Mary of Guise. They had a baby girl, Mary, and when only 6 days old James died leaving, notionally, a 6-day old Queen Mary. So in fact until Mary, Queen of Scots, came of age, regents ruled in her place and sometimes even her mother ruled.

So Mary Guise (the Queen mother) was ruling Scotland with French support.

We must understand that this Scottish-French alliance was really annoying to most Scottish nobles and roused much opposition. Remember, there was local support for the teaching of reform among the people, and rising opposition to Catholicism. There was support because of good Lollard-tradition preaching, inspiration from the martyrdom of George Wishart, Luther’s reformation tracts from the continent, good theology from Geneva, as well as Knox’s ‘secret visit and preaching tour’ from Geneva. It wasn’t safe to make a public tour, but Knox did come over quietly in 1557. oppostion sh nobles and roused much opposition. There was local support fo

When I say that this Scottish-French alliance was really annoying to most Scottish nobles and roused much opposition – the FEAR was that Scotland would become a province of France.

There was growing support for reform in towns and boroughs, but the Regent Queen was becoming less conciliatory now. Fears increased when news emerged that in April 1558, Mary Queen of Scots married the heir to the French throne.

But then, a trigger: Walter Milne (or Mill), a frail old man of 82, was consigned to the flames at St Andrews at the instigation of Archbishop John Hamilton whose family was next in line to the throne. Milne was a former priest who had converted to the Reformation. His burning raised such an outcry among the people that it did much to spread the faith for which he died.

While there were no more martyrdoms in Scotland, matters were coming to a head as the popularity of reform increased. Dundee in the east organised themselves as a Reformed church. Ayr in the west was not far behind. The excesses of the French army of occupation and Scottish patriotism aided change.

In May 1559 Knox returned to Scotland at the request of the Lords of the Congregation, a group of the Protestant nobility who had come together the previous year. They had renounced the Roman communion and with that committed to the pure Gospel. They also pledged to provide in every parish for the reading of the Bible and passages from the English Prayer book of Edward 6th until such time as preaching in public was permitted. This development shows how things had progressed from private meetings of believers to a determination on the part of significant leaders to see a Reformed church throughout Scotland.

The Queen Regent reacted against the preachers, the Protestants mobilised and there was an uneasy truce in May 1559. Then the Regent was suspended by the Lords of the Congregation on October 1559 with a view to establishing a provisional Protestant government. An English army came to the aid of the Scottish Protestants, and the Catholicism sustained by French interests now collapsed. It was supplanted by Protestantism of Calvinistic stripe. The Regent died in June 1560, and the Treaty of Edinburgh, signed in July 1560, gained the withdrawal of both the French and English troops. Francis 2nd of France, the husband of Mary Queen of Scots, conceded the right to the calling of a Scottish Parliament to commence in July.

So, did you catch the irony and strangeness here? A French King, via a declaration from his French Palace, gives the right for the Scottish parliament to meet in Edinburgh. Oh little did the French court realise what they were doing. Oh, how thankful we are that Mary didn’t return to claim her Scottish throne just then … but waited. What a glorious providential moment.

b) The Reformation Parliament

The terms of the Treaty of Edinburgh specifically left religious questions to be submitted to the ‘intention and pleasure’ of the king and queen. However, this was for the present ignored, as Mary Queen of Scots was not going to approve.

Hastily, the Scots seized the moment and got busy.

[What do you need? When you start a church … from scratch?]i) the church needed to know what it believed

By mid-August 1560 a Confession of Faith was adopted – remarkably prepared by ‘the six Johns’: John Knox; John Winram (1492-1582) a former Augustinian prior; John Spottiswoode (1510-85), of the parish of Mid Calder; John Willock (d.1585), a former Dominican friar; John Douglas (1494-1574), provost of St Mary’s College in St Andrews; and John Row (c.1525-1580), sometime procurator at the papal court in Rome.

A week later (before the end of August 1560) the Reformation Parliament abolished the jurisdiction and authority of the bishop of Rome, declared all acts ‘not agreeing with God’s word and now contrary to the confession of our faith’ passed in the reign of James 1st and subsequently, to be of no force or effect and forever abolished.

The papal sacraments, especially the mass, were forbidden to be practised, with penalties as high as death for a third offence.

The Confession was produced in some haste and contains 25 Articles. All the characteristic protestant emphasis on original sin, atonement, unmerited grace, justification by faith alone, predestination and the verbal inspiration of scripture are there. Highlights:

- Scripture is regarded as the supreme and final authority and consistent in itself, and in place of the church as the infallible interpreter, the Spirit of God is the One who illumines and enlightens in the truth.

- The atonement of Christ is regarded as sacrificial, penal and substitutionary, and the doctrine of unconditional election is upheld.

- While not a separate topic, justification by faith is maintained and shown to be a result of a spiritual renewal which also leads to holiness of life.

The Scots Confession may not elaborate any of its doctrines with the precision and fullness we would like. At some points the arrangement appears illogical and the movement of thought confusing. But, it’s Reformation teaching through and through.

ii) the church needed to know best practice

The population of Scotland in 1560 was around 800,000 and there were over 3,000 in the Roman Catholic clerical establishment. The reformed church consisted of about 1,000 parishes needing about the same number of ministers. Five of the eleven serving bishops conformed to the Reformation, three serving actively in the reformed ministry. Within a year or so of the Reformation parliament about 240 men were serving either as ministers or readers in parishes. Of the ministers most had conformed to the new arrangements, and some had been preaching before the upheaval.

The ‘readers’ were persons appointed ‘where no ministers can be had presently’. They were to read the prayers printed in ‘the Book of our Common Order’, that is, the order of service first published by Knox and others at Geneva in 1556, as well as the Scriptures. The expectation was that the readers might ‘grow to greater perfection’ and be able to be admitted to the ministry in the regular way.

Progressively improved and enlarged, and including the entire psalter in metre, the Book of Common Order was published in 1564 for use throughout the church. Within another ten years most parishes had a minister or reader.

First Book of Discipline

Already in April 1560 the Lords of the Congregation had called for a statement on the reformation of religion in Scotland. The first draft of what became known as the First Book of Discipline was made about this time. It covered a wide range including doctrine, national education, poor relief and finance. In January 1561 the final version appeared, written by the same six Johns already mentioned, and was adopted as a platform of church organisation and vision for the future.

The Book of Discipline did not elaborate a full system of church government although the essence of Presbyterianism was there with a congregational eldership and a General Assembly. The twice-yearly synods which existed before 1560 continued, at least from 1562, so there were the basics of conciliar church government.

Highlights of The Book of Discipline:

- it insisted on ministers called by God and elected by the people;

- it also introduced the offices of elder and deacon, subject to annual election;

- there was to be public worship twice on each Lord’s Day (morning and afternoon) and, particularly in major towns, services on other days also;

- public catechising of children was a marked feature of the afternoon service on the Lord’s Day, while marriages took place within the morning service;

- there was to be a regular weekly meeting of the parish minister and elders of one or more neighbouring congregations, called the ‘exercise’, for discussion of Scripture, and men with potential for ministry were also to attend and participate.

Knox and his fellow leaders, having repudiated diocesan episcopacy, were well aware of the need to provide some kind of unity and oversight between parishes in particular regions, and to provide for sound teaching. Given the shortage of qualified ministers the matter was resolved pragmatically by the appointment of superintendents.

And therefore we have thought it a thing most expedient at [or, for] this time, that from the whole number of godly and learned men, now presently in this realm, be selected ten or twelve (for in so many provinces we have divided the whole), to whom charge and commandment should be given to plant and erect kirks, to set, order and appoint ministers as the former order prescribes.

Moreover, a superintendent was not only to consult and deliberate with other ministers and elders in dealing with unsatisfactory ministers or readers, he himself was subject to the censure and correction of the ministers and elders, and was subject also to regular scrutiny by the church Assembly.

Almost overnight, the Scottish Church rejected transubstantiation, denounced the mass and replaced the seven sacraments of the old church by the two dominical sacraments, baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Out went Latin read services, priesthood delivered grace, altars, the hearing of priestly confession, the cult of Mary and the saints, the celebration of holy days and feast days, prayers for the dead, belief in purgatory, the sign of the cross, crucifixes, images and elaborate ritual, surplices (or choir dress) and Eucharistic vestments, organs and choristers, the plainsong of great churches and the silence of poor churches.

In came a simple service based on preaching, Bible study, prayers and the metrical psalms sung to popular tunes, and with this, active participation by the people, who, no longer passive spectators, were encouraged to sing God’s praise and, seated corporately at tables, to receive both wine and bread at communion.

So, by the end of 1560, the Scottish Reformed Church suddenly had formulated what it believed and how it should practice. It was a sudden, thorough, deep Reformation.

But then … comes Mary.

c) Mary Queen of Scots

Mary’s husband died at the end of the year and she returned to Scotland the following August at the age of 18. But she was too late. While Mary was a traditional Catholic, reform had captured the hearts of the people. Mary Queen of Scots, raised Catholic and married a French prince, was due to return and claim the throne, and turn Scotland against reform. But, what is Scotland, now?

Mary in Scotland: AD 1561-1568

Mary, Mary, quite contrary,

how does your garden grow?

With silver bells, and cockle shells,

and pretty maids all in a row.

Like many nursery rhymes, it has various historical explanations. These include:

- one theory sees the rhyme as connected toMary, Queen of Scots, with ‘how does your garden grow’ referring to her reign over her realm, ‘silver bells’ referring to (Catholic) cathedral bells, ‘cockle shells’ insinuating that her husband was not faithful to her, and ‘pretty maids all in a row’ referring to her ladies-in-waiting

Mary returned as the Catholic monarch of a kingdom which had adopted the Protestant faith. She returned as a pious ‘Christian’ determined to go to mass in a country where the mass is outlawed. Conflict is inevitable, in a very personal clash between John Knox and his queen.

Knox vs. Mary

Mary’s seven years in Scotland were a period of extraordinary drama, of which her personal confrontations with John Knox at Holyrood are only the first instalment; they are recorded in detail by Knox in accounts which do nothing to conceal his own ferocious rudeness to the young queen.

However, things were never smooth for our man: By then end of this tumultuous year (1560) his wife Marjory died leaving Knox with his two sons aged 2 and 3 to look after. She was only in her mid-twenties. Knox was devastated.

John Knox returned to his main calling: preacher of the Word of God. He was preacher at St Giles church in Edinburgh, where he remained for most of the remaining years of his life.

He spent a good part of it quarrelling with Mary: Mary, Mary, quite contrary. At least four times John Knox, fiery Protestant preacher, was summonsed to appear before Queen Mary, while she attempted to discipline him.

4. John Knox and his later years

Knox married again to Margaret Stuart at the age of 50 and she was still a teenager. It was ironic for Knox’s long-time rival Queen Mary because Margaret Stuart was her (distant) cousin. She was a loving and faithful wife who supported Knox in his ministry. They had three daughters.

Ill health plagued him in later years. But he taught and preached whenever and wherever he could. But he was clearly weakened by years of attacks on his integrity and threats of violence and then a stroke. His last ministry was at St Andrews. In latter days he’d sign his letters: ‘John Knox, lying in St Andrews, half dead’.

A young ministry student reports on the weakened Knox, still preaching: though weak, he thundered. Saying how that in the pulpit, after a slow start, he would then become enlivened …

‘he became so active and vigorous that he was like to ding the pulpit in blads and then fly out of it’

ding the pulpit in blads = knock it into pieces

Death

The day before Knox died, at age 57, he urged his friends to live for Christ. He had been wrestling with God in prayer and said: ‘I have been in heaven’. As Knox lay dying on his bed he asked his wife to read aloud the 17th chapter of John’s gospel, saying: ‘Go read where I cast my first anchor.’

John 17:1,2 … After Jesus said this, he looked toward heaven and prayed: ‘Father, the hour has come. Glorify your Son, that your Son may glorify you. For you granted him authority over all people that he might give eternal life to all those you have given him.’

When he could no longer speak, he held up two fingers to show he still had faith, and shortly afterward he left this world for his eternal home.

Knox was clearly a man of great courage and one man, standing at the open grave of Knox said: ‘Here lies a man who neither flattered nor feared any flesh.’

One of Knox’s last prayers:

‘Lord, grant faithful pastors, men who will preach and teach, in season and out of season.

Lord, give us men who would gladly preach their next sermon even if it meant going to the stake for it.

Lord, give us men who will hate all falsehood and lies, whether in the church or out of it.

Lord, grant to your struggling church men who fear you above all.’

Another:

‘Be merciful, Lord to your church, which you have redeemed.

Give peace to this afflicted country.

Raise up faithful pastors who will take charge of your church.

Lord, grant us true pastors for your church, that purity of doctrine may be retained.’

5. Assessment of Knox and his work

The exact extent of Knox’s influence on his contemporaries and posterity is a matter of debate, but there can be no doubt that he came to be seen as the leading figure in the Scottish Reformation, playing a major role in the overthrow of Roman Catholicism and the establishment of the Reformed Church. While Scotland might have had some form of Reformation without Knox, it was from him that the Scottish Reformation received much of its character and direction.

a) His life and influence

It is said of Knox that in reforming a church he formed a nation and there is considerable truth in that saying. Whether people like the influence or not it is clear that even to this day the impact of Knox’s life and work is part of the whole framework of Scottish life. He brought back to Scotland the ideal of a return to apostolic authority in faith, worship and discipline. The aim of Knox and his companions was at getting down to bedrock and, when they reached it, seeking to build upon it. They would not rest satisfied with a basis of Church life which was a compromise.

b) His writing

Knox did not see himself as an academic theologian or writer, though he was a prolific letter writer and many of these are contained in his collected writings. After a time in Geneva Knox returned and wrote ‘A Faithful Admonition’ which was an attempt to argue that England was repeating the idolatry of Israel of old. It was also a direct attack on Mary Tudor. In his ‘First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women’ (published in Geneva) Knox argued that having a female sovereign was against natural law and also against God’s law. His longest theological work was a defense of the Reformed doctrine of predestination. However, Knox is certainly best known for his ‘History of the Reformation in Scotland’.

c) His preaching

Knox was pre-eminently a preacher – one appointed ‘to blow his Master’s trumpet’, as he said (cf. Ezekiel 33).

This is one of the many facets of Knox’s life which must be given prominence in any consideration of his work, because it was central and also because of the effectiveness of his preaching. His calling was to be a preacher, not a theologian. That is why he considered his main duty was ‘to blow my master’s trumpet’. It may seem surprising that we only possess one printed sermon from his pen. However we do have other fragments of his preaching recorded in his History of the Reformation, in publications such as his exposition of Christ’s temptation in the wilderness, and many references in his letters to the task of preachers and their message.

That he was a vigorous preacher there is no doubt. James Melville tells of listening to him in St Andrews in 1571. Knox had to be helped to the church and lifted into the pulpit. ‘I had my pen and my little book, and took away such things as I could comprehend. In the opening up of his text he was moderate the space of a half-hour, but when he entered to application, he made so to shudder and tremble, that I could not hold a pen to write.’ The ailing Knox, says Melville, ‘ere he had done with his sermon, he was so active and vigorous that he was like to ding that pulpit in blads and fly out of it’

What lessons do we learn from this man? Take home lessons?

- Reading Knox all over again, I find that I’m being blessed by the following two characteristics:

- Knox’s patience and strength under trial; that in the midst of suffering, and he had plenty: months and months as a galley slave, years of ill health, loneliness after the death of his young wife, and all through his ministry bearing the hatred of many who opposed him, YET he remained strong and used his diligence and energy to serve his master without wavering

- Knox’s strength and depth of his devotion to God; he loved God with deep feeling and with passion and, as a consequence … we remember the value of talking straight while not setting out to ‘be rude’ – Knox’s passion for God was such that he did not fear man … there were no gray areas for him … saw himself solely as a servant of God; when he preached he said: “I quake, I fear, I tremble’; too often we think the measure of success is the praise of fellow man, but Knox saw success of pleasing God; his indignation wasn’t rudeness but it was something like his Master’s spirit expressed in John 2 when he drove out the money changers who had made his Father’s house a den of thieves instead of a house of prayer

- Then, reading Knox all over again, I find that I’m grateful to him for practical and godly change he brought about in the life of the Christian church. i.e. because of his strength under trial and his deeply felt devotion to the glory of Christ, he persevered until change was effected in the church, eg:

- the value of the family – under Knox’s leadership, Scottish families were transformed. Family worship entered homes, Psalms sung, the Bible read;

- the value of local, congregationally elected leadership – the church was transformed, Presbyterian, governed, not by hierarchy but by local elders and deacons

and all this written by Knox in English, not Scottish of the day – with the vision that one day all Britain will be united around the Reformation gospel. Knox was truly an international Christian reformer, so he wrote in a language that would untie, not divide.

So, under God’s sovereignty, Reformation was brought to Scotland – the most thorough Reformation of any country. And all with little civil unrest or loss of life.

John P Wilson

(July 2017)

APPENDIX

Four major documents of the Scottish Reformation

- The Scots Confession

See Henderson’s summary statement: ‘The Scots Confession is neither so carefully complete nor so rigidly systematic as the Westminster Confession. It was produced by men who were worried, not so much by the niceties of theological controversy, as by practical problems of the Christian life, worship, government and discipline. It was somewhat hastily put together, though the writers were far from being unprepared for such a task, the Reformation being by this date no new thing, and the documents and practice of other Churches quite familiar. From the scientific point of view, the Scots Confession is unsatisfactory on account of repetition, vagueness and imperspicuity’.

Several of its characteristics are:

a) Its Order

As compared with the Westminster Confession it is notable that the doctrine of Scripture does not come first, nor does it have any lengthy elaboration. The first eleven chapters cover basic Christian doctrines that had been taught for centuries. However from chapter 11 onwards the environment in which the Confession was produced manifests itself. There is a polemical tone to it, and three chapters are devoted to the Sacraments while other Christian doctrines are not mentioned at all.

b) Biblical Emphasis

There is a very strong biblical emphasis throughout it, with many quotations or allusions to biblical passages. This aspect reinforces the composers’ desire expressed in the preface to conform their teaching to a biblical position.

c) Theological Approach

As compared with other Reformed confessions the Scots Confession is not as systematic in its approach. Rather, it is a combination of systematic and biblical theology. This comes out in the treatment it gives in chapter 4 to the revelation of the promise. While not explicitly mentioning covenants, there is recognition of the various periods of Old Testament history, and of the expectation felt by true believers regarding the coming of the Messiah. In the following chapter on the church, it summarises biblical history from Adam to Christ, with special mention of Abraham, the Exodus, and David.

d) Polemical Element

It should not be surprising that in the era of the Reformation credal statements should be polemical. But this aspect is remarkably restrained throughout the Scots Confession. Compared with language used elsewhere, the Confession is very mild in its condemnation of other positions. The Catholic positions are contradicted in various chapters (see chapters 9, 11, 18 & 23), but positions held by other Protestants are also refuted (see chapter 21 regarding the Zwinglian doctrine of the Lord’s Supper, and chapter 23 regarding the Anabaptists’ refusal to baptise infants.

e) Covenant Theology

There is no explicit teaching on the covenants, but clearly covenant theology was understood, and it is there by implication in chapter 4. Loose Phrasing At times loose phrasing occurs (e.g. chapter 3 with the reference to the image of God being ‘utterly defaced in man’). But loose phrasing can be excused because of the circumstances in which the Confession was framed. It was not framed in the quiet chambers of Westminster, but in the heat of battle and with great haste.

f) Scottish Characteristics

There is little to mark out the Confession by Scottish language or distinctive teaching. The positions taken seem to be mainly from Calvin’s positions as expressed in the Institutes. If there is anything Scottish it is the warmly evangelical tone of the Confession that represents the position of Knox and his associates.

- The First Book of Discipline

It was easier to deal with doctrine than with polity. The First Book of Discipline took months to prepare and shows that despite the political victory in 1560 there was not a clear-cut and detailed protestant program.

The Scottish Reformation had many formative influences from the Continent, though it also had opposition from the remnant Catholic party and also the individualists like Thomas Methven, who rejected both papalism and Calvinism alike. However, the sects posed no real threat to the Reformation in Scotland.

The proposals in the First Book of Discipline were influenced by Bucer’s ideas on many points, but were much more radical when it came to matters like the benefices. Bucer wanted to retain the old system, while the Scots’ reformers aimed to replace it with a totally different system.

It was an impressive but untidy document, which mirrored many of the strengths and weaknesses of the Protestant movement itself. It was as much concerned with a vision of a new society infused by the Spirit of God as it was with order in the church.

While the First Book was very clear on many points, yet there were other points where it was ambiguous. James Kirk lists three:

- Little thought was given to the wider structure of the national church.

- The relationship between the reformed church and the government was not spelled out in enough detail.

- The First Book did not set out clearly enough how the finances from the benefices could be reallocated .

- The Second Book of Discipline

There was an experiment with episcopacy in 1572, which was rejected by the Assembly in 1576. This move in the Episcopalian direction was largely the result of the desire of Regent Morton to see the polity of the Scottish church conformed more to the English pattern.

In 1576 the move was made to draft a new constitution for the church, ‘Heads and Conclusions of the Policy of the Kirk’, The Second Book of Discipline. This has often been attributed to Andrew Melville, but he was only one of about 30 who worked on it. Most of those who participated in the drafting had belonged to the Reformation party of 1560. Regional committees were set up, and then their work was revised by other Assembly committees, and finally the Assembly itself debated the issues.

The Second Book of Discipline is concerned with doctrine, discipline, and distribution. Flowing from this division comes the three offices in the church: ministers, elders, and deacons. The word bishop was reserved for the minister, and as all the offices were a vocation they were considered as being for life, and therefore ordination by the imposition of hands was appropriate.

The government would not fully endorse The Second Book of Discipline, so the Assembly went ahead as best it could, and in 1581 registered the SBD among the Acts of the Assembly.

- Knox’s Liturgy

The English Second Book of Common Prayer of Edward VI was widely used in Scotland, but it was replaced in 1562 by the Book of Common Order, which is sometimes called Knox’s Liturgy. This name is because it was used in the congregation in Geneva where Knox ministered to the English exiles. In 1562 it was authorised for use in connection with the sacraments and then in 1564 for the ‘common prayers’ as well. It was used for the reading of prayers when ministers were unavailable.